Shedfilling: hoarding and the circular economy

We’re getting an extension built here at Terra Infirma Towers and I’ve been beavering away clearing the back yard, basement and my current office to get them ready for the builders to move in. What I’ve found incredible is the sheer amount of stuff I had hidden away for the best part of 20 years.

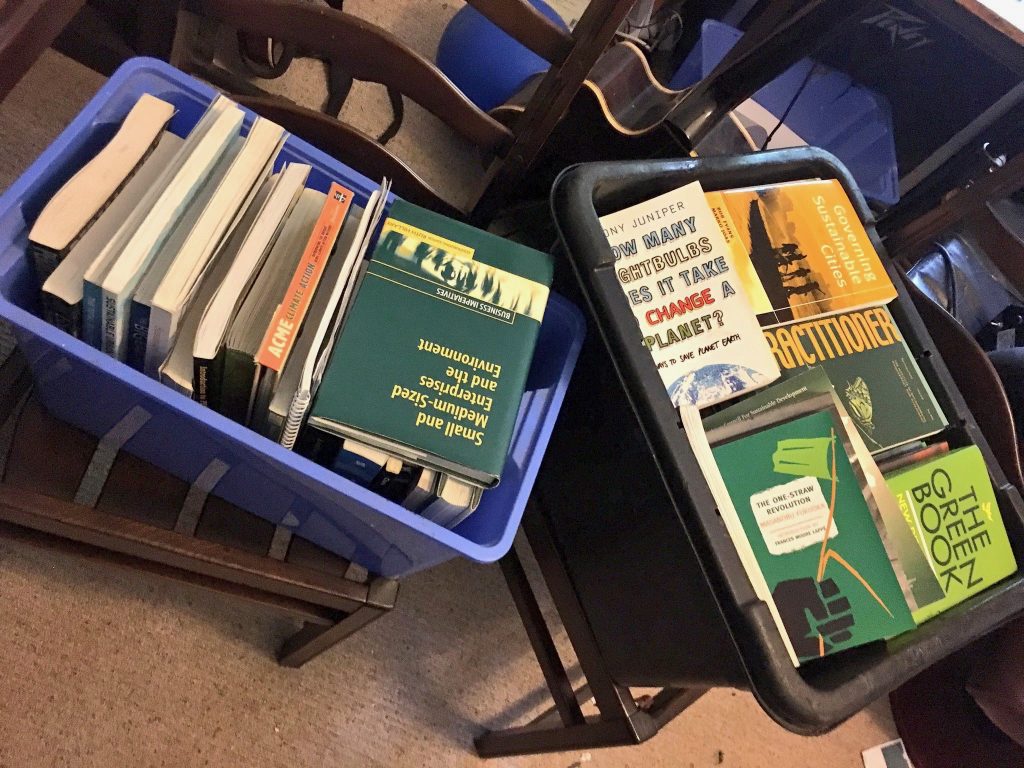

I did feel a bit funny about chucking the bench vice I clumsily welded together on an apprenticeship almost 30 years ago in the metals recycling skip at the Civic Amenity site, but it didn’t work and the metal is better used as something else (I kept the functional if impractical nutcracker and the practical toolbox for nostalgia). Likewise in my office there’s a huge number of books and I’ve decided to weed out the ones I’m really never going to go back to and get them to charity shops (the ones pictured I’m keeping).

So this got me thinking: how much stuff is in the limbo between use and disposal? How many sheds, cupboards, basements and drawers are full of stuff which is never going to be used again – or recycled into component parts? Google didn’t throw up an easy answer – searching for ‘stockpiling’ took me further into the crazy world of ‘prepping’ than I ever wanted to go. But a 2007 EPA study (quoted here) suggested that a whopping 75% of computers, tablets and phones ever bought in the US are simply gathering dust.

I suspect that the length of the stockpile cycle for electronics is much shorter than for my vice (which must have sat around doing nothing in at least half a dozen homes), but that is a huge amount of precious and/or useful metal doing nothing in a relatively concentrated state while we mine for more from the earth’s crust.

For the circular economy to function efficiently, we need to recover as much of this stuff as possible as quickly as possible for reuse or reprocessing. Product take-back schemes are the obvious solution for obsolete electronics and various retailers will collect anything from old trainers (I have loads of ’em) to Christmas cards and I use Freecycle for working stuff. But those are still niche services for those who can be bothered.

To make the cycle work, we need to be making recycling as easy, if not easier, for the punter than purchasing the bloody stuff in the first place. I can envisage a system where smart reprocessing systems make micropayments for useful materials – not enough to encourage burglary, but enough for the average person to make the effort.